"Those who rape know damn well that no means no. That's what makes it worthwhile for them. They're not confused by the idea that some women are supposed to play hard to get."and

"Rapists are sensitive to labeling themselves as such. However, they invariably know, and enjoy, the fact that they're forcing the woman."and

"The typical rapist attacks serially and is only stopped with a jail sentence, but yes, the 1st time he has non-consensual sex makes him a rapist, and not just "technically."and

"I've heard from a couple of different sources that rapists are like hunters stalking for their next victim. I heard a statistic that although about 7% of men have attempted or committed rape, the number of women raped is much higher because these men have more than one victim. This statistic comes from a study of young men that ask about some of their behaviors, like, do you get excited/hopeful/aroused when a woman gets sloppy drunk. The study does not use the word rape because, as you point out, even the East Coast Rapist can't call himself that. However, the 7% of the men's answers point to raping behaviors."

To which, I had to respond:

I'm going to try and find some empirical sources, but until then I'll supplement with my own anecdotal evidence. I have a number of friends that have been raped. I also know quite a few people that work for the Sexual Assault Response Prevention Program (SARPP) at my school.

Recently, my school participated in The Clothesline Project which involved survivors of sexual assault writing on t-shirts and hanging them up for all to see. By the end of the day there were hundreds. Some of them were talking about how they didn't let the assault break them, some were talking about how they can't trust men anymore. But most of them involved calling attention to their attacker, either by name, fraternity, or some other means. Almost all of them mentioned that this guy was a friend. I couldn't even count the number of times I saw written "my rapist doesn't know he's a rapist." Because rapes are underreported.

Recently, my school participated in The Clothesline Project which involved survivors of sexual assault writing on t-shirts and hanging them up for all to see. By the end of the day there were hundreds. Some of them were talking about how they didn't let the assault break them, some were talking about how they can't trust men anymore. But most of them involved calling attention to their attacker, either by name, fraternity, or some other means. Almost all of them mentioned that this guy was a friend. I couldn't even count the number of times I saw written "my rapist doesn't know he's a rapist." Because rapes are underreported.

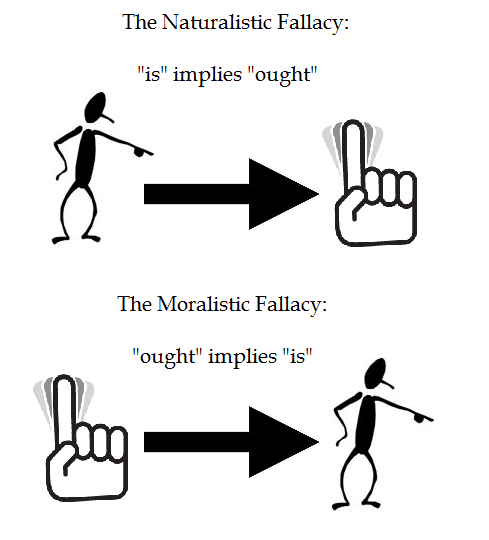

Why? Because most of the time, they cannot be proven. And people do not want to believe that the quarterback, the valedictorian, or the shy kid could take advantage of a girl. But they do. These men are not predators in the sense that they consciously hold a hatred of women, get off on hurting people, or sit waiting for their next victim. No, these are merely men to whom the notion of consent doesn't matter.

Part of this is because our culture has inculcated the idea of "playing hard to get" as the article mentions. Regardless of whether or not women do this, most men have the idea that women do. And this means that when they are met with resistance, they just push harder. It is very different from "I am planning on raping someone tonight because that's what turns me on." Those types are rare. It is rather, "But if she didn't want to have sex then why was she making out with me? She totally wanted it, I just helped convince her."

This is misogynistic thinking fueled by the simple idea that women are there for us to consume and use; that they are not autonomous beings who have their own beliefs, desires, and fears. And in that moment, they believe that you're not going to stop, they're afraid that they're right, and they desire to get out. There isn't the black and white line between "rapists" and "everyone else" that most people think there is. To claim that is to be part of the problem; to be a rape denier. To deny the fact that hundreds and thousands of women are assaulted every year by their acquaintances, friends, and even partners. To claim that "rapists" are merely psychopaths as opposed to regular males who merely don't understand consent and happen to be in a situation to exercise their power is blind yourself to the majority of sexual assaults.