The issue with many of the beliefs that people hold is that they're not simple matters of taste. I may dislike Nickelback as a band, but the fact that certain people enjoy Nickelback is of no concern to me. Why? Because people liking Nickelback has no effect on my life or that of anyone else who may dislike them. Now we have established a criterion for when beliefs held by others should matter: if the beliefs cause people to act in ways that they otherwise would not.

For example, if a person is secretly racist we may find this deplorable, but if they never act on it, in what way could we know? The chances of someone actually being racist and never acting on it are probably impossible, since these beliefs manifest themselves in subtle ways that we are generally not aware of. But the point is that beliefs lead to actions. And if these actions can hurt, oppress, and generally cause harm to society, then there is warrant for us to care what other people believe.

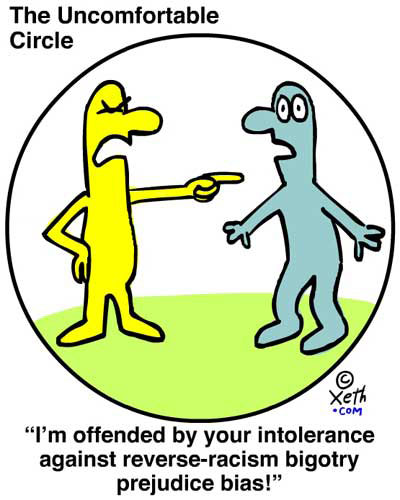

I've had people tell me that I am just as bad and intolerant of the people I am speaking out against. They've told me that just because I disagree with someone doesn't make them bad, or wrong, or give me a reason to question their beliefs. Let me illustrate a picture: does a person who is racist (something we in the liberal western world tend to think is pretty bad) have the right to say that an anti-racist is discriminating against them? That doesn't really make any sense. The people who fought to free the slaves and for civil rights aren't people we look back on and say "Geez, couldn't they just leave other people's beliefs alone?" I speak out when I think people are being oppressed or harmed.

How do we define harm? There are various ways, so I'll give some examples. When children are taught that humans walked with dinosaurs, the KKK were nice people, and gay people are as awful as rapists and child molesters, their education is harming them. When parents allow their children to die by refusing medical treatment in favor of prayer, their spiritual belief is harming them. When psychics rob people of their money by claiming they can perform spiritual healing, claim they can talk to dead loved ones, or just provide false info to further their personal gain, their credulity in charlatans is harming them. This is just a short list. I could write about a hundred more ways in which people are harmed every day due to the nature of their beliefs.

I can imagine someone saying at this point, "Okay, so some people believe some stupid things. But my beliefs don't harm anyone. For example, I don't believe in evolution and it doesn't hurt anyone."

I will attempt to illustrate that the effects of holding a view such as creationism aren't immediately obvious, but just because they aren't immediately obvious doesn't mean there can't be latent harm. For example, if there were only one person who didn't believe in evolution we wouldn't have a problem, but the fact remains that half of Americans reject evolutionary theory. And furthermore, any argument that goes, "Well, me alone doing this action isn't hurting anyone, therefore it is fine," is not justifiable when we imagine the consequences, were everyone to do it. This known as the tragedy of the commons. Therefore, yes, if you and just you alone decide to litter, you won't destroy the world, but if everyone does? Well, we're still trying to fix that mistake.

An anticipated objection at this point is "I understand that littering is bad, but you haven't demonstrated that not believing in evolution is bad."

Allow me to do so.

Sometimes the harm of a belief is that it manages to oppress a group for no other reason than to oppress them. For example, to argue that racists are oppressed by civil rights would be quite silly. The oppressors do not get to say they are being oppressed when people speak out against them. Otherwise we would have an infinite regress of each person claiming that their rights were violated when another person disagreed with them. The buck has to stop somewhere, and it stops at the opposition. You don't get to simply oppose those who disagree with you ad infinitum; you defend your original position. So when people have beliefs such as an idea that a particular race is inferior their own, they might do something like enslave that race. Even after slavery has ended, the dominant group might continue to oppress that race. We clearly understand the link here between belief and action, and while it isn't one person who keeps the wheels of oppression turning, the mindset that "Racism is okay, even if I'm not a racist" does nothing to help those who are oppressed - it does just the opposite.

So here's how the argument breaks down: sometimes the effect of a belief is apparent, as in:

Racist beliefs --> Racist behaviorSometimes it's way more latent, as in:

Science denial --> Kids dying from parent's belief in spiritual healing and lack of belief in modern medicineSometimes the path has many stops, as in:

Evolution denier --> Uninterested in science --> Not enough employment science/technology related fields --> No cure for cancer yetSometimes it's a small part of a larger problem, as in:

No issue with racist beliefs --> A system that continues to run based on oppressionIn short, beliefs matter a lot. They have an effect we are unable to see most of the time. We should not write them off as necessarily harmless for that reason alone. I consider myself a feminist, yet for so long I spent time participating in behavior quite clearly anti-feminist and lo and behold, I was completely unaware of it. It wasn't until my consciousness was raised by the efforts of other individuals that I was able to implement change.

Don't be afraid to question things. It's the only way we can get true social change.